Three years ago, the art world was buzzing and works were fetching records sums. Then the recession struck. How can the market recover? And will the slump change art itself?

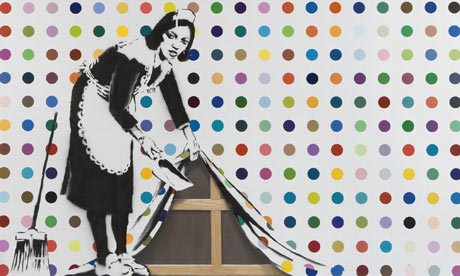

The way things were ... Keep It Spotless, a Damien Hirst work defaced by Banksy, which sold in New York early last year for $1.8m. Photograph courtesy Damien Hirst/Sotheby's

Ancient and Modern is a tiny contemporary art gallery in east London, on the kind of street where the rows of betting shops and scruffy caffs might blind the uninitiated to its aching trendiness. Three years ago, when the art market was booming, I visited the gallery on the eve of its opening. One of the partners bullishly told me what he predicted for the future: "In three years, either we'll be ready to get a bigger space, or I'll get a job at Costa Coffee." In fact, he has left the gallery, and is now a freelance writer and curator. His business partner Bruce Haines is still here, slogging on. He pours me water from a San Pellegrino bottle. "Actually, it's not San Pellegrino," he confesses. "It's Waitrose Basic. But San Pellegrino looks better – I decanted it." Times are tough: how long before Aldi's own-brand takes its place?

Back in 2006, it seemed that everyone was opening a gallery. In tatty-fashionable east London, you could carouse your way through a dozen private views in an evening, and the scene was cool and confident. At the top end, things were seriously lavish: that year, gallerist Victoria Miro turned over the top floor of her huge space for a banquet for 160, in honour of artist Grayson Perry. London had been anointed the centre of the European contemporary art market. And that market was rocketing: according to Art Market Research, which gathers data on the art trade, contemporary art prices rose 313% in the two years to September 2008. If the art market has been like a wave, swiftly gathering height and force, it reached its towering peak on 16 September last year – the day Damien Hirst's Sotheby's sale grossed £111m, the day after Lehman Brothers collapsed. And then the wave came crashing down. In the past year, according to Art Market Research, contemporary art prices have dropped by 63%.

Haines has had a turbulent 12 months. After a "pretty terrible" October, the gallery had a "totally terrible" time at Art Basel Miami in December, the big international fair. Early 2009 was bleak: "We were rattling around in the empty, echoing halls of the art world." Haines sold a house he owned in Wales, left his part-time curating job, and threw himself into the gallery. This week he is at Frieze art fair, showing an exhibition of keepsakes and ornaments collected by the parents of artist Alan Kane. "The irony is, we're doing a show that's not for sale – we must be mad," he says.

Amid all this uncertainty, what are we to make of the prospects for art – and for artists? Jeremy Deller, who won the Turner prize in 2004, actually sells very little. Most of his work is project-based, relying on grants; he sits slightly outside the vagaries of the market, and is not one of those few artists who have made fortunes. "It's like the housing market," he says of the boom. "It can be quite stressful if you're not in it, but you can still see it's totally overblown. The art market has obviously been overblown – that's why I don't go out much. I don't want to hear how much everyone has been making." A boom, he thinks, "can be bad for certain kinds of art and artmaking. A lot of bad art is made to cash in. Art fairs can encourage flashy, showy, grabby art – art that's just a photo opportunity." Artist Grayson Perry says of the downturn: "It winnows it out, doesn't it? I'm thinking wheat, chaff. There were some terrible, estate-agent types coming into the art world. You felt there were more chancers, of all kinds – artists, collectors, gallerists. I prefer my art world towards the dusty-museum end of things. Hopefully, it will return to a place where the principal validators of art are academics and serious people, and not Russian oligarchs."

Has the recession changed art? If playwrights (Lucy Prebble, David Hare) and film-makers (Michael Moore) have been quick to make work examining the financial crisis, there is little evidence yet of a similar trend in visual art. (There are exceptions: the Danish collective Superflex has made a series of short films about the downturn, screening on Channel 4 this week, in which the artists treat the crisis as a form of psychosis to be treated by a hypnotist.) But the narrative structures of film and theatre are designed to dramatise and explain. Art is less direct. While not explicitly about the market, there has been a great deal of work in recent years that has appropriated the strategies of the boomtime commercial world. The YBAs cheerfully lassooed the power of the market for their own ends – from Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas's 1993 Shop, to the glittering climax of Hirst's auction last year (itself billed as a work of art, entitled Beautiful Inside My Head Forever).

Will this kind of work disappear as the downturn continues? It is striking how tired the post-Warholian tendency looks today, placed in its art-historical context: compare the somewhat weary reviews of the new Tate Modern exhibition Pop Life, featuring work by Jeff Koons and Hirst, with the response to this year's Turner prize show – a quieter, less commercial, but more thoughtful kind of art. "I suspect artists will feel they'll not have to make work to sell in a gallery, work that's easily framed," says Deller. "I've been waiting for a backlash against the YBAs, a complete revolution against their way of doing things. People have essentially been using the same strategies. The recession might help – the art from that era emerged from a recession, after all." He pauses. "I'm still waiting for someone to use the internet, really use the internet. We're still in a post-Warhol era. We haven't got beyond it." Hirst is too anomalous an artist to be a weather-vane, but he is an astute reader of the mood of the times. His output has shifted from the ultimate boom-time symbol of the diamond skull, to the slow and solitary practice of painting (last November, he made redundant an unconfirmed number of assistants). But this week's attempt to place himself in art history's pantheon, with a new painting exhibition alongside the old masters at the Wallace Collection in London, looks bombastic and irrelevant. And the truth is, there has always been a lot more to British art than the YBAs, even if they make the most noise.

Artist Richard Wentworth, until recently head of the Ruskin art school in Oxford, says he detects something of a return to DIY, to the skill of one's own hand, among the young artists he knows. "There's a reduction in the idea that someone else will do it," he says (Anish Kapoor and Jeff Koons, among others, continue to run large studios). He describes the young graduates he knows as tribal, non-conformist, a little bit under the radar – his analogy is to 18th-century Quakers. He points to a pop-up exhibition being run by young artists in an empty house in Mayfair: "The general sense of resourcefulness has been raised," he says.

'There is no apocalypse'

What impact has the downturn had on the big auction houses? Francis Outred, head of contemporary art at Christie's, describes last year's October auctions as "pretty devastating", the first three months of 2009 as "like doomsday". This week's auctions are very different from those of recent years – much smaller, "soberly priced", he says. Artists whose prices have particularly suffered, he says, include American giants Richard Prince and Jeff Koons, and Hirst. "A lot of the market revolves around supply and demand," he says (many people have argued that Hirst has overproduced). The market for Banksy has also tumbled. "Speculators filled out the market up to the £500,000 level, and created mini-markets. The street-art phenomenon was built on speculation," says Outred.

Nonetheless, this doesn't look like being a collapse on the scale of the early 1990s. Gallerist Sadie Coles, who represents artists Sarah Lucas, Richard Prince and Carl Andre, remembers that recession vividly: she was working at Anthony D'Offay, then one of the few London contemporary galleries. "His staff went from 32 to 14," she says. This time round, Coles is pushing on through the downturn.

But if the YBAs were born out of a recession, they started from a very different place. There was no Tate Modern, no Frieze; being shortlisted for the Turner prize did not guarantee fame and controversy. There were very few collectors of new art, very few commercial contemporary art galleries. The rich filled their country houses with antiques. All that has changed – and it will, I suspect, be a lasting cultural shift. But if the art market is down, it is not out. There are still a lot of people who want to look at contemporary art, and who have the means to buy it.

A fortnight ago I met Stuart Shave, who owns the London gallery Modern Art. "The eagerness of the press to find a crash doesn't bear much relation to the workings of the art world," he says wearily. He admits he has been "working three times as hard for fewer sales" – but there is no apocalypse, he says. For him, the days when selling anything at all was a cause for celebration – "we barely knew where to find the machine that printed invoices" – are not so distant a memory that his head was turned by the speed of the boom. What worries him more is the fate of the public sector. "The main concern about the recession is what it means for museum acquisition. Recently, a large majority of sales have been to museums. Except in this last year, they just haven't been." Susanna Beaumont, who owns Edinburgh gallery doggerfisher, agrees: "Individuals will rally but institutions' ability to acquire work will be threatened."

I asked Neville Wakefield, who curates a series of special commissions for Frieze, what he thinks will happen next in the art world, and he points me to New York, to the Bruce High Quality Foundation – a collective of anonymous young artists who, with the help of an unnamed benefactor, have just set up the Bruce High Quality Foundation University in Tribeca. It is free to attend, unaccredited, and its curriculum is pretty much made up as it goes along. Offering courses with such titles as Occult Shenanigans in 20th/21st Century Art, and What's A Metaphor, the university describes itself as "a 'fuck you' to the hegemony of critical solemnity and market-mediocre despair". On their website, they have posted a fantastical story about a post-apocalyptic world in which artists hole up in the Guggenheim and defend the world against a zombie attack, bowling Brancusi sculptures at them and feeding them Hirst sharks. If this is the future, then it's critical, alternative, underground, funny – and defiantly independent.

via: the guardian.

No comments:

Post a Comment